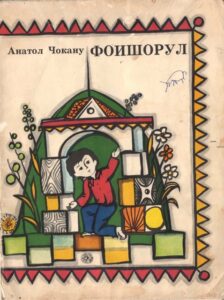

ФОИШОРУЛ ВЕСЕЛ / ВЕСЁЛЫЙ ТЕРЕМОК

ФОИШОРУЛ ВЕСЕЛ / ВЕСЁЛЫЙ ТЕРЕМОК. Версурь пентру грэдиница де копий/Для дошкольного возраста. Алкэтуитор/Составитель: Анатол Чокану. Традукэтор/Переводчик: Виталие Балтаг. Пиктор/Художник: Анатолий Смышляев. Едицие билингвэ/Двуязычное издание. Кишинэу, Литература Артистикэ, 1984. Legătură: MediaFire