Отфрид Пройслер.

Мика врэжитоаре.

Повестире-басм.

Десене: С. Букур, Ю. Леу.

Тэлмэчире дин л. русэ: Г. Водэ.

Кишинэу, Литература Артистикэ, 1986.

Legătură: MediaFire

О мие ши уна де нопць.

Повешть алесе.

Тэлмэчире: Нина Искимжи.

Префацэ: Михай Чимпой.

Презентаре графикэ: Исай Кырму.

Кишинэу, Литература Артистикэ, 1977.

Legătură: MediaFire

Ион Крянгэ.

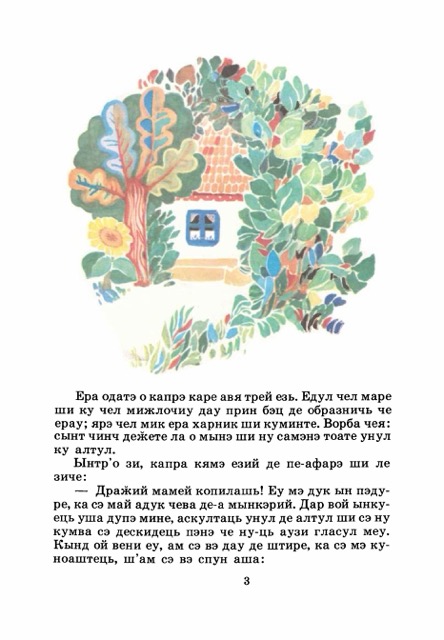

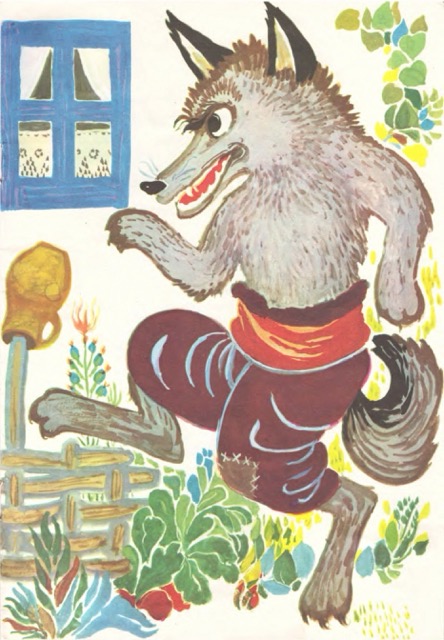

Капра ку трей езь.

Повесте.

Пиктор: Игор Виеру.

Кишинэу, Литература Артистикэ, 1988.

Legătură: MediaFire

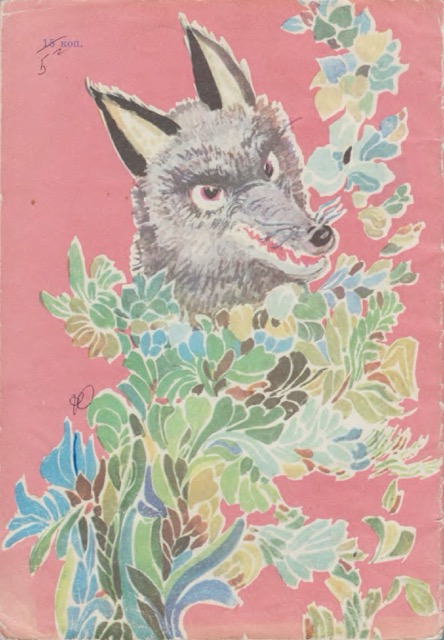

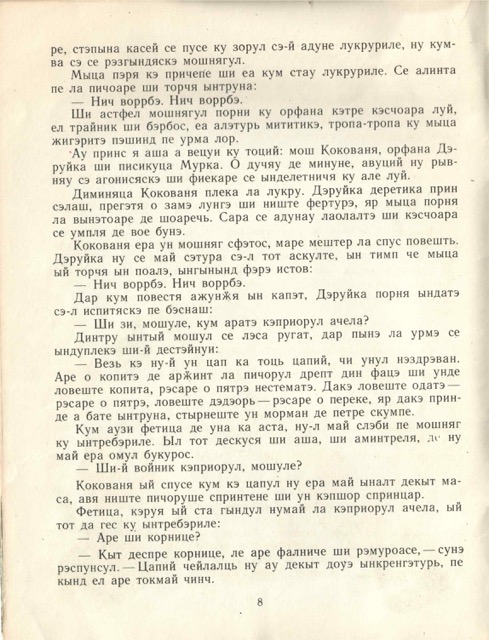

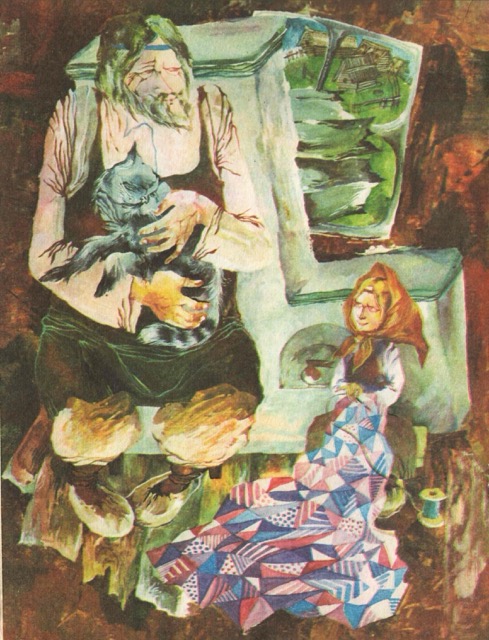

Павел Бажов.

Копита де арӂинт.

Илустраре: В. Бульба

Традучере де Игор Крецу.

Кишинэу, Литература Артистикэ, 1979.

Legătură: MediaFire

Вино, повесте, вино!

Повешть ши провербе але попоарелор Етиопией ши Суданулуй.

Повестите пентру копий де Л. Любарская.

Традусе де Григоре Ботезату.

Пиктор: Е. Камин

Кишинэу, Лумина, 1967.

Legătură: MediaFire

Инелул фермекат.

Повешть киргизе.

Тэлмэчире де Нина Искимжи.

Презентаре графикэ де Г. Остапенко.

Серия “Библиотека пентру тоць”, 24.

Кишинэу, Картя Молдовеняскэ, 1972.

Legătură: MediaFire

Масаллар: Гагоуз халк масаллары/Масаллар : Гагаузские народные сказки.

Литературная обработка: Николай Бабоглу.

Художник: Дмитрий Савастин.

Кишинев, Hyperion, 1991.

Download: MediaFire

Download: Library Genesis

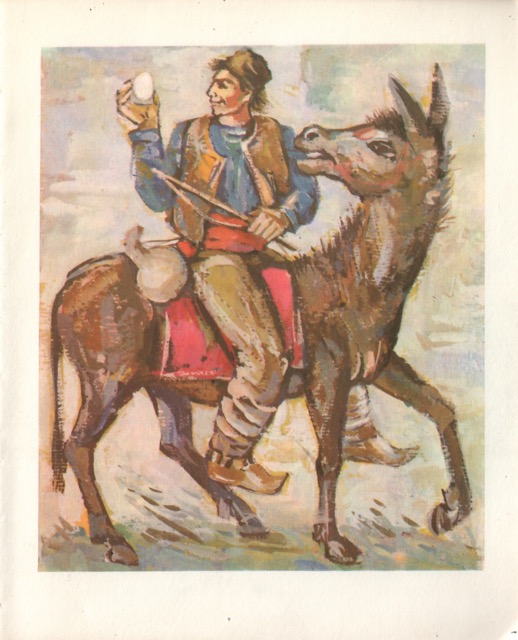

Moldavian Folk Tales.

Collected and retold by Grigore Botezatu.

Second revised and enlarged edition.

Translated from the Moldavian by Dionisie Badarau.

Illustrated by Leonid Domnin.

Kishinev, Literatura Artistika, 1986.

Link/Legătură: MediaFire

Legătură: Library Genesis

FOREWORD:

Moldavia is a country of vine-yards and orchards, the homeland of outlaws and of the legendary heroes Grigore Kotovski and Sergei Lazo, the abode of nostalgic doinas and lively horas. Thousands of springs murmur on its expanses, the ancient forests rustle unceasingly, the pensive Nistru bears its waters among rocks, while villages gleam white everywhere, bathed in sunlight, and the vine, called “the strength-giving bush”, gathers the sun’s rays, the earth s vigour, and the Moldavian’s toil in its golden grapes day by day.

This “threshold of Paradise”, as Moldavia is poetically called in the delightful old folk song “Mioritsa”, has become famous not only for the beauty and bounty of its land, but for the treasures of its spiritual culture.

The heroic-epic songs about Novak and Gruia, Brave George, Codreanu, Corbya, Buzhor, Tobultock and others are an artistic summing-up of life. They show the great deeds of the epic heroes, their ardent hatred of the people’s foes, their longing for freedom, their uncompromising struggle against exploitation, and love for their Motherland. ,

Everybody grows to love the folk stories about Prince Charming and Leonora Golden-Locks, about Hop-o’-my-Thumb and Dragan-the-Bold, about Brave Pepper, and Laurel-the-Monster, the fairy tales about the clever peasant girl, about Pepelea and the greedy landlord, and the humorous tales about Pacala and Tyndala and others.

It is to the folk narrators that we owe the preservation of these fairy tales, to the craftsmanship in their retelling, and to the gift of inventing them. Differing in their repertoire, in their creative character, and in their manner of retelling, these tolk narrators are well known all over the country, enjoy enormous esteem, and are listened to with great love, … .

In the old folk stories the role of the messenger who comes to those retelling the o d spells is fulfilled by some supernatural fantastic being. This poetic character is usually a whitebearded old man, who hands over a golden goblet full of honey, and a shepherd s flute to the narrators, and conveys the mystery of the tale s texture to them. There was such a belief that the shepherd, who told beautiful new fairy tales evening after evening for a certain period of time, was rewarded: a magic sheep appeared in his flock, and with it the gift of predicting the future.

The fairy tales themselves were seen in the artistic imagination of the people as changing into fires. In a Moldavian fairy tale published at the end of the XIX-th century it was said that once in a village three travellers stopped overnight at a house and each of them told a fairy tale. Later on the fairy tales turned into three fires and protected the house from everything evil. “That is why”,’the folklorist E. N. Voronka remarked in 1930 (as she had heard from a narrator in the village of Makhala), “it was very well to retell long fairy tales in the evening, because… such fairy tales surrounded the houses three times, and nothing evil could approach them”.

The retelling of fairy tales has been thoroughly studied, in close connection with the history of the people, and with their development, determined by definite economic and historical conditions. This statement is not intended to demonstrate the protective function of retelling stories, as a means of driving off evil spirits, but to underline the symbolic meaning of those old beliefs, that the fairy tales told during long autumn and winter evenings are seen as protectors of human dwelings, driving away the evil and soaring up into the sky like fires, dissipating the darkness with their light. The protective power of the light comes, of course, from the perennial spring of the moral contained in the fairy tales, from the inspiration of the great deseds, and from the cleverness and the valour of the epic heroes. This is fully shown by the fairy tales gathered in this collection.

The fairy tales represent an important portion of the folklore heritage of the Moldavian people. Their collection and publication began long ago. Many motives from popular epic prose creations were included in old Moldavian literature, and in books on folklore.

The Moldavian fairy tales attracted the attention of Russian and Ukrainian writers such as A. S. Pushkin, A. M. Gorky, M. Kotsubinsky and others. M. Gorky heard from folklore narrators the legend about Danko who tore his heart out of his chest and raised it high like a torch to illuminate the way for his fellows.

Many Moldavian fairy tales have been published in Russian by N. Gerbanovsky and A. I. Yatsmirsky. These publications had a popularizing character.

The Moldavian folklore is rich in fantastic fairy tales, short stories, legends, tales about animals, and in anecdotes. The fairy tales with their bright ideal of justice, of the defeat of all evil forces, of optimism, and of good deeds, are connected with the longing and dreams of the oppressed in the past. The positive characters reach their happy destiny due to their bold and uninterrupted struggle. The wisdom and heroism of a character are appreciated very high and well-portrayed in these works.

The gatherings where fairy-tales were retold were very numerous in the past, and more often than not consisted of evening meetings when the village people sat all together. They constituted the specific repertoire, when people met for collective work. This work, and especially the spinning, was accompanied by jokes, tricks, songs, humorous stories, riddles and, of course, by fairy tales.

Thus everybody is welcomed at the evening parties in the Moldavian villages, where the thread of the fairy tales is spun, and the sweet voice started in remote times is heard up to this day.

The fairy tales, together with doinaș, folk ballads, sayings and riddles form the spiritual wealth of the people, are full of admonitions, of lofty ideas and unsuspected beauties, since, after all,

A fairy tale is a fairy tale, And to tell it I should not fail. How everything happened and came to be, As one night in the village they told it to me.

Gr. Botezatu.

Повешть Популаре Молдовенешть.

Кулесе ши прелукрате де Григоре Ботезату.

Презентаре графикэ: Л. Домнин.

Кишинэу, Лумина, 1972.

Legătură: MediaFire

Картя де фацэ презинтэ о кулеӂере де повешть, сноаве ши глуме, кулесе дин несфыршита комоарэ а креацией популаре.

Ын фаца ноастрэ се периндэ тот фелул де ынтымплэрь фантастиче але унор ерой, каре се афлэ мереу ын луптэ: ероий позитивь се афлэ ын луптэ дряптэ ку чей негативь. Дезнодэмынтул нарациуний, адуче ынтотдяуна ун триумф ал бинелуй асупра рэулуй.

Деши фантастиче, тоате ачесте елементе изворэск дин реалитатя ынконжурэтоаре ши рефлектэ ынтр’о формэ симболикэ фелул де вяцэ ши фелул де а гынди ал попорулуй, атитудиня луй фацэ де реалитатя ынконжурэтоаре, драгостя фацэ де Фэт-Фрумес ши Иляна Косынзяна, каре сынт ынфэцишэторий попорулуй ши ынтрукипязэ челе май алесе калитэць але луй.

Pe acest blog a mai fost publicată o carte de povești populare moldovenești – Повешть популаре Молдовенешть, Литература Артистикэ, 1988.